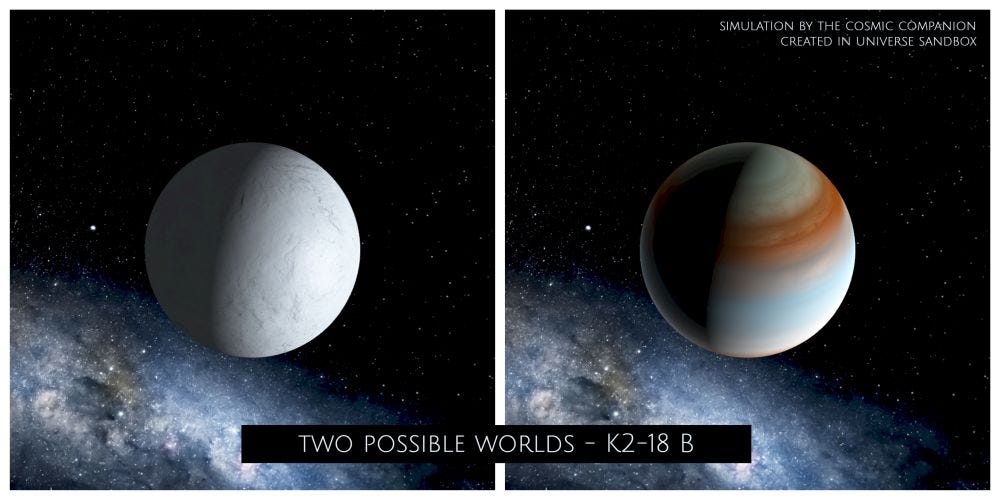

Roughly twice as large as Earth, with 8.6 times the mass of our homeworld, this exoplanet orbits within the habitable zone around its star, K2–18. This region of a solar system, sometimes called the Goldilocks zone, is the distance from a star that is neither too hot nor too cold, for liquid water to exist on the surface of a planet. “To establish the prospects for habitability, it is important to obtain a unified understanding of the interior and atmospheric conditions on the planet — in particular, whether liquid water can exist beneath the atmosphere,” Nikku Madhusudhan of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy, who led the new research, stated. Read: [Massive planet that would dwarf Jupiter has been discovered in our galactic neighborhood] Researchers at the University of Cambridge in England developed simulations of K2–18b, determining that this world is able to house large reserves of water beneath its dense atmosphere of hydrogen. “We wanted to know the thickness of the hydrogen envelope — how deep the hydrogen goes. While this is a question with multiple solutions, we’ve shown that you don’t need much hydrogen to explain all the observations together,” said Matthew Nixon, a PhD student at University of Cambridge. Following the discovery of K2–18b in 2015, astronomers began studying the system in more detail. Just two years later, a second super-Earth was spotted orbiting the same star. That planet, K2–18c, is closer to its parent star than its companion. The star around which these worlds orbit, K2–18, is a small, cool, red dwarf, roughly 40 percent as massive and large as our own sun. This exoplanet straddles the line between a super-Earth (a larger version of our homeworld) and a sub-Neptune (a largely gaseous world). To determine the nature of the planet, the team created simulations based on data provided by the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher (HARPS) planet-finder in Chile. Mini-Neptunes are thought to consist of a solid core of rock and iron, covered by a layer of water at high pressures, surrounded by a thick atmosphere of hydrogen-rich gas. If this layer is too dense, it would raise temperatures of the water above the point where life as we know it is likely to survive. Machine learning was used to determine the mass of K2–18b. This value, combined with the radius of the exoplanet, allows researchers to calculate the density of the planet. This figure (around 2.67 grams per cubic centimeter — about half as dense as Earth) provides vital data information on the composition of this world. “With a bulk density between Earth and Neptune, K2–18b may be expected to possess a H/He envelope. However, the extent of such an envelope and the thermodynamic conditions of the interior remain unexplored,” researchers wrote in a journal article published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. If K2–18b possesses a thick atmosphere similar to Neptune, the chances of complex molecules developing there — never mind life — would seem remote. “In a hydrogen-rich atmosphere, the temperature and pressure increase the deeper you go. By the time the rocky core is reached, the pressure is expected to be thousands of times higher than the surface of Earth, and the temperature can approach 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit,” Laura Kreidberg wrote for Scientific American in September 2019. This study suggests the exoplanet likely resembles either a rocky world with an atmosphere or a water world, covered with a thick layer of ice. Haze may be present in the atmosphere, although no evidence for such a layer was conclusively found by the team. Significant quantities of water were found in the atmosphere of K2–18b, along with lower-than-expected concentrations of methane and ammonia. This anomaly could be, but is not necessarily, the result of life on that world.

When the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) launches (hopefully sometime in 2021), it will open its powerful eye to exoplanets, as well as other targets. This next-generation telescope should be able to tell whether K2–18b is a water world or a world which might feel a little bit more like home. Red dwarf stars are attractive targets for astronomers studying exoplanets, as the cool temperatures and low masses of these stars provide a favorable environment for finding exoplanets. Even the planets which seem most “habitable” among the thousands of worlds we have found are still hellish places for any life that evolved on Earth. And K2–18b would still seem quite inhospitable to lifeforms used to the warm embrace of Earth.