They claimed that the brain’s neuronal system forms an intricate network and that the consciousness this produces should obey the rules of quantum mechanics – the theory that determines how tiny particles like electrons move around. This, they argue, could explain the mysterious complexity of human consciousness. Penrose and Hameroff were met with incredulity. Quantum mechanical laws are usually only found to apply at very low temperatures. Quantum computers, for example, currently operate at around -272°C. At higher temperatures, classical mechanics take over. Since our body works at room temperature, you would expect it to be governed by the classical laws of physics. For this reason, the quantum consciousness theory has been dismissed outright by many scientists – though others are persuaded supporters. Instead of entering into this debate, I decided to join forces with colleagues from China, led by Professor Xian-Min Jin at Shanghai Jiaotong University, to test some of the principles underpinning the quantum theory of consciousness. In our new paper, we’ve investigated how quantum particles could move in a complex structure like the brain – but in a lab setting. If our findings can one day be compared with activity measured in the brain, we may come one step closer to validating or dismissing Penrose and Hameroff’s controversial theory.

Brains and fractals

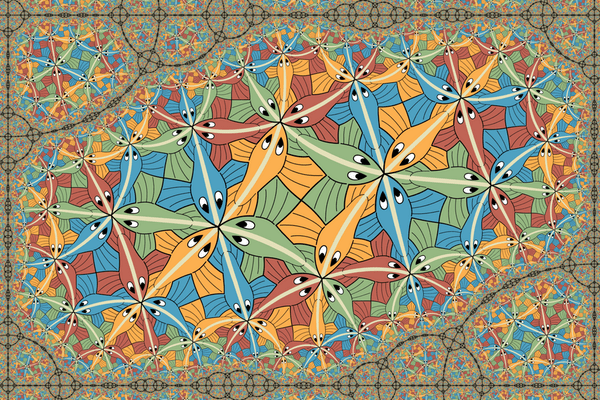

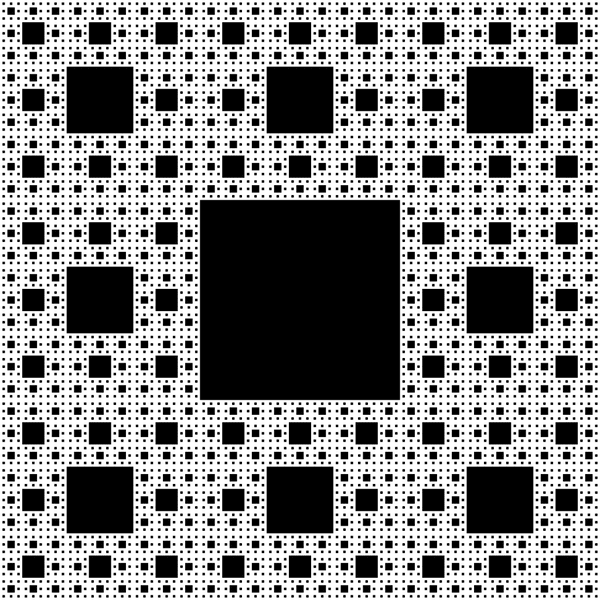

Our brains are composed of cells called neurons, and their combined activity is believed to generate consciousness. Each neuron contains microtubules, which transport substances to different parts of the cell. The Penrose-Hameroff theory of quantum consciousness argues that microtubules are structured in a fractal pattern which would enable quantum processes to occur. Fractals are structures that are neither two-dimensional nor three-dimensional but are instead some fractional value in between. In mathematics, fractals emerge as beautiful patterns that repeat themselves infinitely, generating what is seemingly impossible: a structure that has a finite area, but an infinite perimeter. This might sound impossible to visualize, but fractals actually occur frequently in nature. If you look closely at the florets of a cauliflower or the branches of a fern, you’ll see that they’re both made up of the same basic shape repeating itself over and over again, but at smaller and smaller scales. That’s a key characteristic of fractals. The same happens if you look inside your own body: the structure of your lungs, for instance, is fractal, as are the blood vessels in your circulatory system. Fractals also feature in the enchanting repeating artworks of MC Escher and Jackson Pollock, and they’ve been used for decades in technology, such as in the design of antennas. These are all examples of classical fractals – fractals that abide by the laws of classical physics rather than quantum physics. It’s easy to see why fractals have been used to explain the complexity of human consciousness. Because they’re infinitely intricate, allowing complexity to emerge from simple repeated patterns, they could be the structures that support the mysterious depths of our minds. But if this is the case, it could only be happening on the quantum level, with tiny particles moving in fractal patterns within the brain’s neurons. That’s why Penrose and Hameroff’s proposal is called a theory of “quantum consciousness”.

Quantum consciousness

We’re not yet able to measure the behavior of quantum fractals in the brain – if they exist at all. But advanced technology means we can now measure quantum fractals in the lab. In recent research involving a scanning tunneling microscope (STM), my colleagues at Utrecht and I carefully arranged electrons in a fractal pattern, creating a quantum fractal. When we then measured the wave function of the electrons, which describes their quantum state, we found that they too lived at the fractal dimension dictated by the physical pattern we’d made. In this case, the pattern we used on the quantum scale was the Sierpiński triangle, which is a shape that’s somewhere between one-dimensional and two-dimensional. This was an exciting finding, but STM techniques cannot probe how quantum particles move – which would tell us more about how quantum processes might occur in the brain. So in our latest research, my colleagues at Shanghai Jiaotong University and I went one step further. Using state-of-the-art photonics experiments, we were able to reveal the quantum motion that takes place within fractals in unprecedented detail. We achieved this by injecting photons (particles of light) into an artificial chip that was painstakingly engineered into a tiny Sierpiński triangle. We injected photons at the tip of the triangle and watched how they spread throughout its fractal structure in a process called quantum transport. We then repeated this experiment on two different fractal structures, both shaped as squares rather than triangles. And in each of these structures, we conducted hundreds of experiments. Our observations from these experiments reveal that quantum fractals actually behave in a different way to classical ones. Specifically, we found that the spread of light across a fractal is governed by different laws in the quantum case compared to the classical case. This new knowledge of quantum fractals could provide the foundations for scientists to experimentally test the theory of quantum consciousness. If quantum measurements are one day taken from the human brain, they could be compared against our results to definitely decide whether consciousness is a classical or a quantum phenomenon. Our work could also have profound implications across scientific fields. By investigating quantum transport in our artificially designed fractal structures, we may have taken the first tiny steps towards the unification of physics, mathematics, and biology, which could greatly enrich our understanding of the world around us as well as the world that exists in our heads. Article by Cristiane de Morais Smith, Professor, Theoretical Physics, Utrecht University This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.