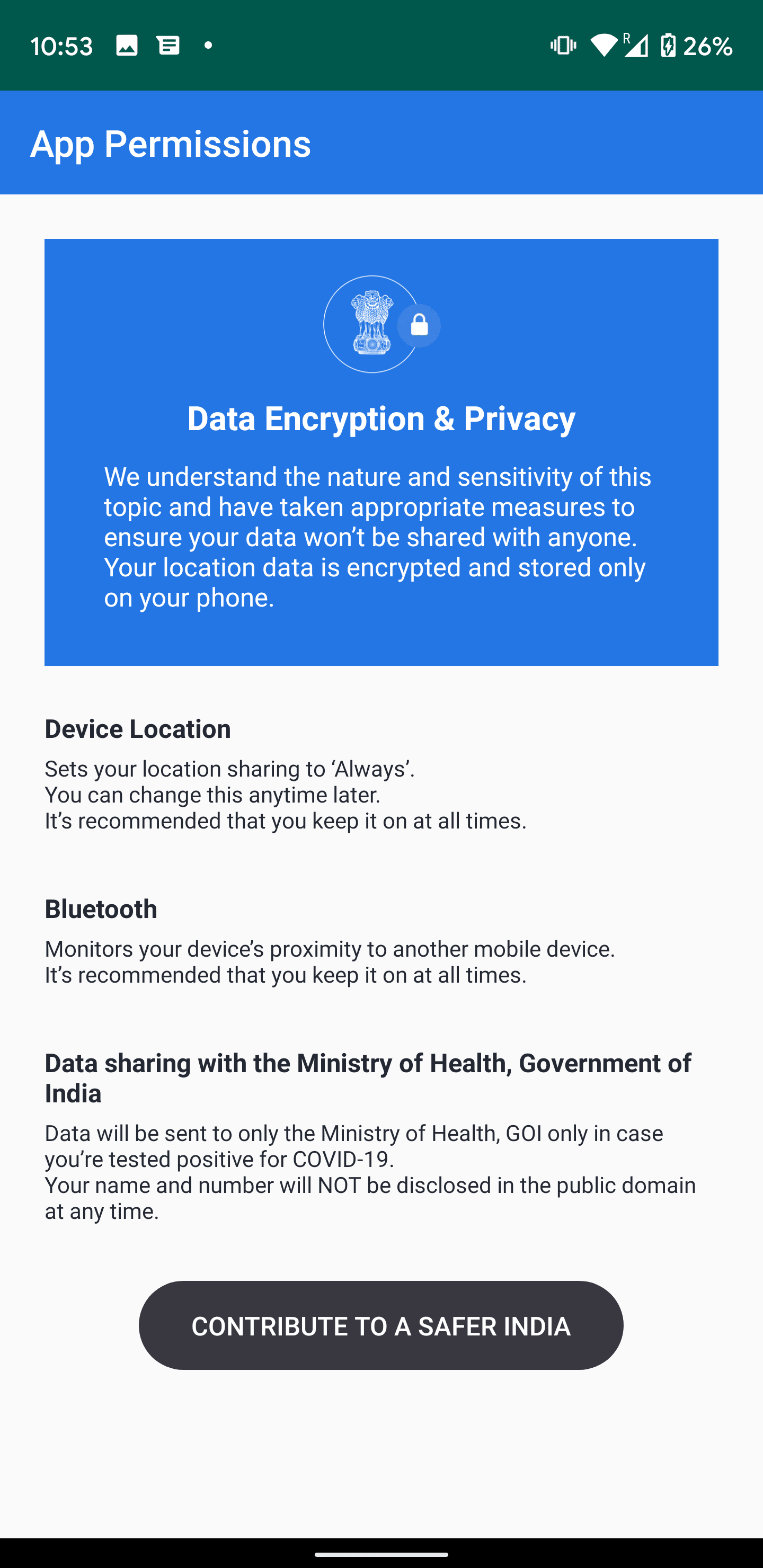

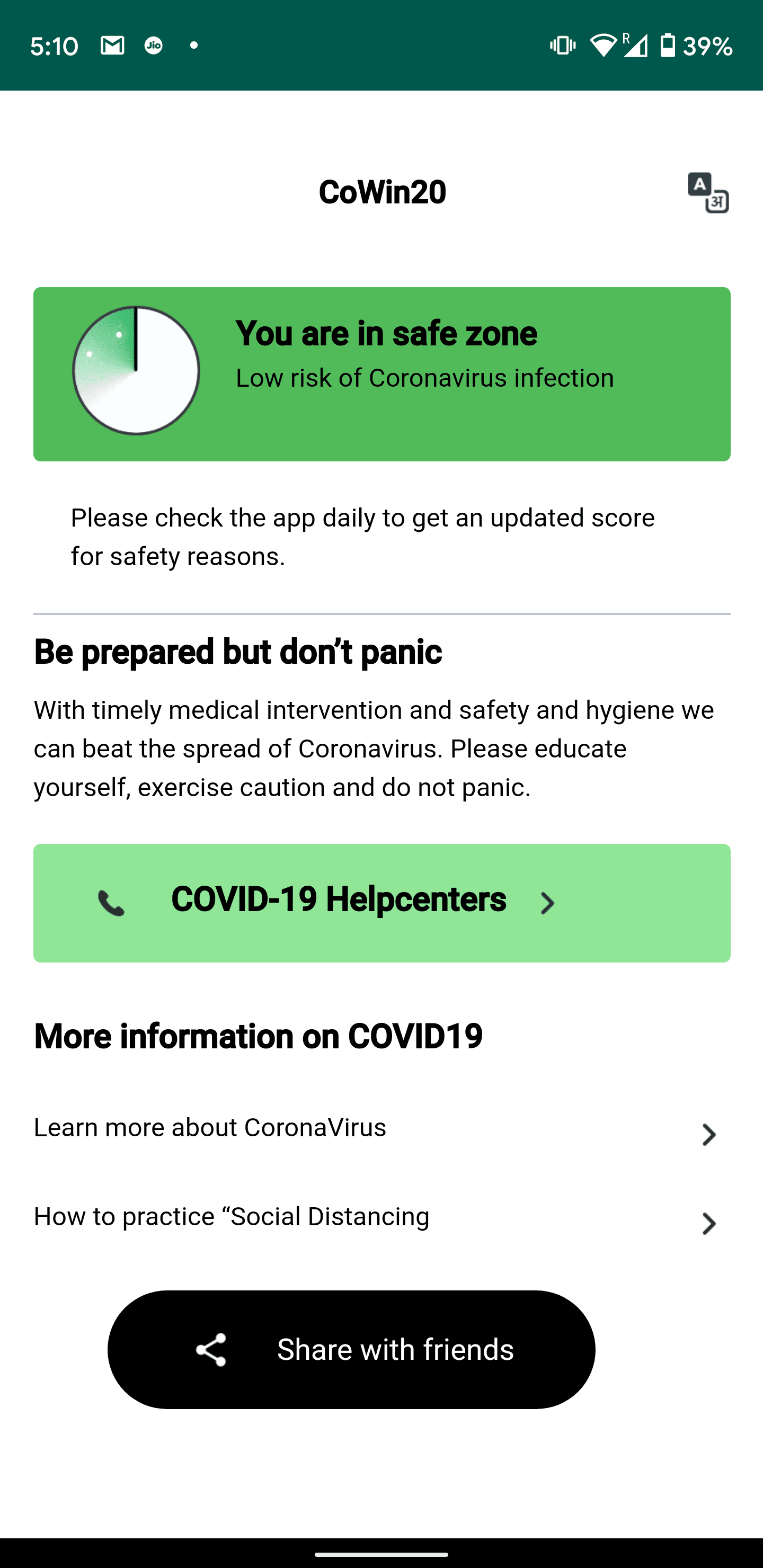

The app is called CoWin-20, and is currently being tested on both iOS and Android. It will track your location and alert you if you are near a COVID-19 infected patient. A report from News18 noted that the testing is limited to a select group of users right now. CoWin-20 will use your location data and Bluetooth to gauge if you’ve been near a person who was infected by COVID-19. It likely determines that by looking through a database of people who have been infected, as well as with one containing individuals’ travel history. It’s also said to be able to tell you if you’re in an area with a high number of coronavirus cases. The app asks for your permission to always access your location data, a step that might raise privacy concerns. However, it promises it to keep your data encrypted and limited to the device; it’ll only share your data with the health ministry if you’ve tested positive for the disease. It isn’t yet entirely clear how the government will track those people and match up their location data in the app. While the app doesn’t reveal much at the moment, the underlying code examined by TNW unearths some interesting features that might be in the works. First, the app will rely on Bluetooth to check if you’ve been within six feet of the distance of an infected person. Second, the health ministry plans to send a notification to anyone who’s been in close contact with anyone tested positive for COVID-19 to get a test done: The code seems to also suggest a map-like feature to trace your location history and people you’ve been in contact with. A notification will then be sent to all of them to get a COVID 19 screening done. Because you happened to be at the gathering, you’ll also get a call informing that you might also have a high chance of contracting it too. This way, you’ll get notified way in advance of the chances of contraction and buy more time to take the necessary steps to prevent it from spreading. This explains why the app might need to continuously track your location. The code also suggests that the app isn’t fully ready yet, and there are parts of it that might take some time to be built out completely. Plus, as this is a beta build, a few features may not be present in the final version. All this works presumably only when a large number of people install this app. So, the government will expectedly promote this app in various ways to get more people to use it. In India, various states have tried stamping people under quarantine with an unwashable ink brand. However, some of them were found to be traveling on trains after being stamped, creating a dangerous situation for others who might get infected. Apart from this, there have been multiple instances in many states where people who were suspected to be COVID-19 positive fled isolation facilities. As such, it stands to reason that the government might want to use an app that can notify authorities if people under quarantine are moving around in public. However, the app also raises a ton of privacy questions, including how long users’ data will be stored, and how it will be secured. The government has been accused of violating citizens’ privacy multiple times. India’s upcoming data privacy law is also under discussion, so there are no safeguards related to data protection at the moment. We’ve asked NITI Aayog, the department behind the development of the app, for more details, and we’ll update the story accordingly. A few other countries have made their own apps to track COVID-19 infected patients. Last month, China launched an app to let people scan QR codes to determine if they were in close contact with anyone who had coronavirus. Earlier this week, Israel released a similar app to help curb the spread of the pandemic. And Singapore recently launched its own tool, which is open source and available for anyone to review. Given the lack of privacy legislation in India, the country’s government would do well to follow Singapore’s lead and adopt an app that can be reviewed by the public for privacy and security concerns. Right now, these government initiatives might be the need of the hour to help control the pandemic. However, privacy experts are rightfully asking questions about what happens to the data post-pandemic, and whether these tools will eventually morph into tools for snooping on citizens.