I had been eagerly waiting to take it out for a spin, and I always imagined the Pixel would be the handset to change my mind about mobile photography. Then I discovered its camera app has no pro mode. The realization made me absolutely dread the idea of going out to shoot the streets. [Read: A love letter to my most loyal companion, the Fujifilm X100F] The thing is, there are so many moving parts behind how a sensor handles image processing: Exposure, shutter speed, white balance, shadows, temperature, sharpening, contrast, noise, and highlights among others. Each camera processes photos differently, which is why you’ll find so many dissimilarities among brands in the final images they produce. The iPhone is notorious for its natural color grading, low contrast, and warmer tones, while the Pixel traditionally accentuates deep shadows, high contrast, a high dynamic range, and cooler temperatures.

This might seem like a minor issue to the average smartphone shooter, but all of these tiny details actually play a massive role in forging a mood in your photography. Indeed, part of the fun of testing out a new camera is figuring out how to bend its processing tendencies to fit your style. The absolute worst nightmare of a photographer who has spent thousands of hours honing a distinctive look is to rely on the camera to do that for them. Developing a personal style is a strenuous and deeply intimate process. It’s about taking risk and failing, over and over again. Until you eventually make it work. Consumer products like the Pixel and the iPhone aren’t designed to fit your style — they’re designed to fit the norm. They’re whipped up to please the masses. They emphasize technical proficiency over distinctive style because the goal is to appeal to as many people as possible.

I can’t blame phone makers for tuning their camera software for what most consumers like, because their goal is to move units. As a photographer, though, I can’t pretend this strategy hasn’t ruined smartphone photography for me. Sure, technical proficiency is important, but intentional aberrations have an absolving quality to them. This isn’t unique to photography either: It’s true for all art. Breaking the rules isn’t inherently wrong. It’s only wrong when you do it without a purpose.

Think about your favorite filmmakers, musicians, or painters. You can probably immediately name the defining features of their art. On a more abstract level, though, these features have become defining only in the backdrop of the larger tradition they operate within. In other words: What makes their style defining is what separates them from the norm — it’s what makes them different. That’s why I despise the idea of letting my phone define my photography. It’s the artistic equivalent of counting on auto-correct to sharpen Kafka’s writing. It’s like Nas penning a verse and asking Alexa to spit it out. (It sounds like I’m comparing my photography to Kafka’s writing and Nas’ rapping. I’m not.)

That’s also why I care about having a camera pro mode as a photographer. I want to shape up my images manually, not have the phone do it for me. But Google doesn’t do photography like that. Instead, it relies on computational algorithms to make all these choices for you. It’s an approach that has earned the Pixel series a reputation as one of the best in the camera department — but also one that inevitably strips images of any creative identity. Computational photography smothers personal style, it kills mood, it erases difference.

All of these things made me hesitant to shoot with the Pixel 4. I knew I wouldn’t find the process fulfilling. Over the five months I’ve had the handset in my pocket, I used it to photograph the streets only a handful of times. I despised every single one of them. Don’t get me wrong: I absolutely love the overall Pixel 4 smartphone experience. Despite its many shortcomings, it was my favorite phone of 2019. It was easily my most trusted tool. I simply wasn’t fond of using it for photography.

So much so that I never even bothered to review the pics I snapped with it. Until last week. It’s not easy to admit it, but I might’ve been wrong about the Pixel 4 all along: I absolutely hated doing street photography with it, but I love everything about the photos it delivered.

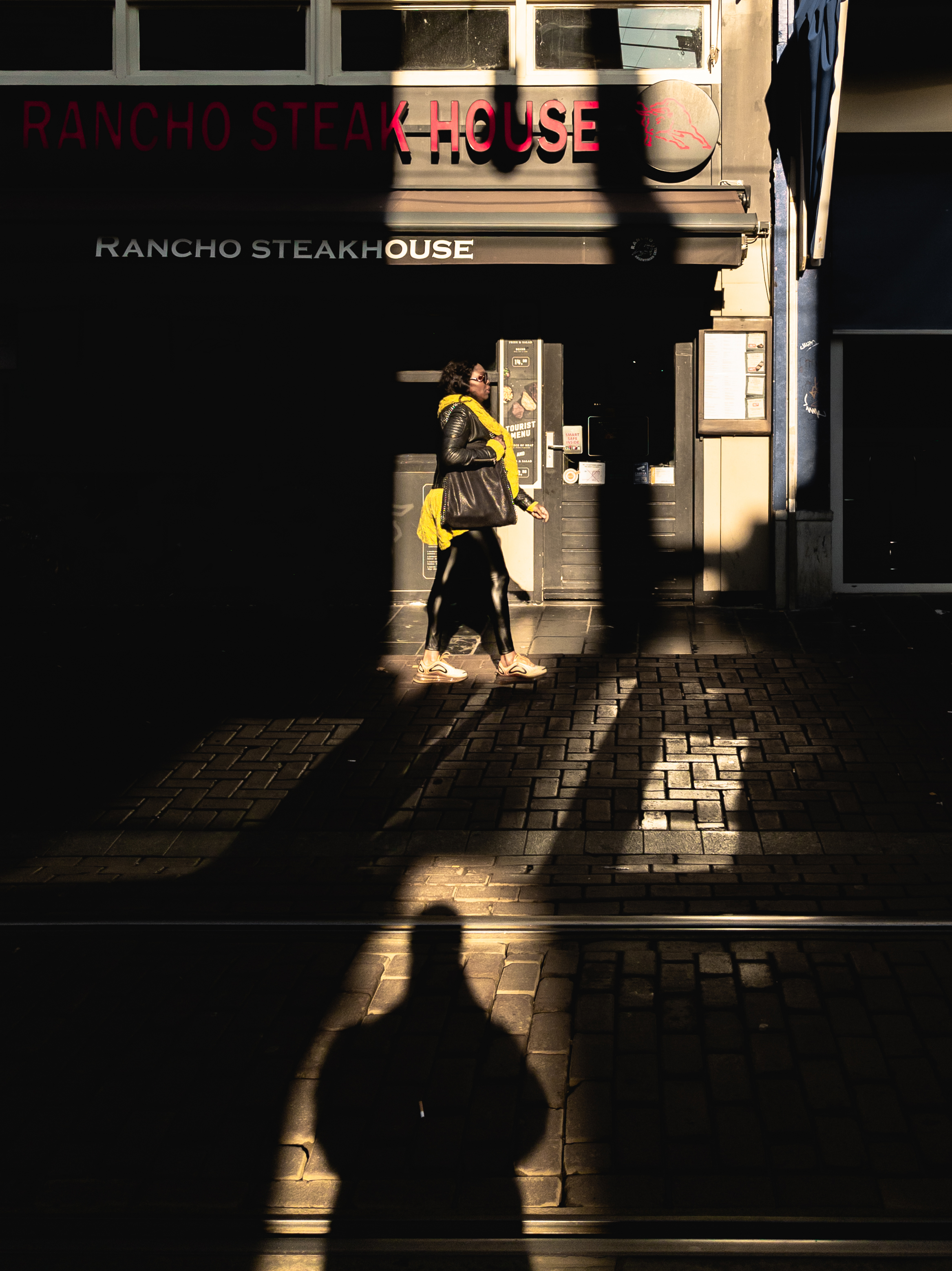

Yes, handling is a huge pain in the ass. You’ll miss a lot of moments if you’re hellbent on using the brightness and contrast sliders in the camera app. Unfortunately, that’s the only way to control how much light you let into the sensor. This leaves photographers with two options: Catch a moment but with settings suboptimal to your personal style (something you can try to salvage in post-production), or adjust the settings and hope there’s another equally gripping moment to capture. Which approach is right will depend on the situation, but these are roughly the main scenarios. Take this shot for instance:

I noticed the way my shadow was cast on the back of this woman created a confusing perspective that makes it seem as if we share the same pair of legs. She wasn’t moving much, but didn’t quite stand still either, which meant that each time she swung her body I had to adjust my position too. That made it difficult to tailor the settings without missing the moment, so I simply trusted Google’s computational algorithms to do it for me. Ideally, the camera would up the shutter speed to accentuate the shadows and capture the subject without any blur. It’s also important to avoid under-exposing the legs, since that would ruin the effect. Fortunately, one of Google’s specialties is high dynamic range, which is precisely what’s needed in a situation like this. I ran the image through Lightroom for some minor adjustments, straightened it up in Photoshop, and the rest is history. That’s one example in which you can actually benefit from Google’s computational photography. Other times, though, you might want to meddle with the settings a little more. Here’s my favorite pic taken with the Pixel 4:

I snapped this still the very first night I went out with the Pixel. I had already been roaming the center of Amsterdam for over an hour, when I spotted someone had left this thoughtful remark on a well-lit wall. “Fuck you” is an interesting phrase. It could be a harsh, personal insult in one situation, and an utterly indifferent throwaway statement in another. Somehow, these fundamentally conflicting sentiments are manifested by the same two words. This is how I see it at least. So how do I reflect this vision in an image? Well, the former sentiment would require a strong human factor in order to translate visually. An angry face staring down the lens, a middle finger pointed at the photographer — these are visual markers that reinforce the ‘Fuck you’ energy. It’s generally not a good idea to seek such reactions when shooting the streets, so I opted for the other approach: Indifference. In my mind, indifference has a lot in common with anonymity. Indifference is faceless, it passes you by without acknowledging you, you notice it, but it doesn’t leave an impression — both parties are disengaged. It’s a fleeting, insignificant of a sentiment, much like motion blur. It’s not tough to set your camera for motion blur. All it takes is lowering the shutter speed until your camera can’t freeze the moment, so it creates a blur. Easy. It’s a bit trickier when you can’t manually set the shutter speed, though. In the case above, I wanted the ‘Fuck you’ on the wall to be clear, but also let enough light into the sensor to capture an indiscernibly blurred face in the foreground. To achieve this effect, I focused on the wall and slightly overexposed the lights by bumping the brightness slider. From my previous attempts, I noticed the Pixel automatically lowers the shutter speed when it focuses on static subjects, so I expected any passers-by in the foreground to leave visible motion blur, which is exactly what happened. It took a few attempts, but I eventually got the shot (I also did some creative editing in Lightroom and Photoshop to underscore the overall mood). Was it a bit of a hassle. Sure. Was it worth it? Totally.

Unlike Huawei’s P30 Pro, which had a rage-inducing delay between releasing the shutter and actually capturing an image, the Pixel 4 feels ultra snappy. It also has the color science down, which simplifies the post-production process. Editing images in Lightroom and Photoshop is refreshingly delightful — especially compared to the P30 Pro. One unusual thing I noticed when working with Pixel raw files is that Lightroom automatically increases white tones by 15, reduces black tones by 5, and boosts clarity by 8. In fact, those are the default settings for all Pixel raw files. For those unfamiliar with the terms, this practically means your images will have brighter lights and darker shadows. It’s not a nuisance at all since you can tinker with those settings manually — it’s more of an observation. The photos are also remarkably sharp, which is a testament to Google’s software capabilities and yet another proof you don’t need to play gimmicky spec games to produce excellent image quality.

Is it better than an actual camera? No. You’ll always find minor imperfections if you go pixel-picking. But on Instagram, where the maximum resolution is 1,350 x 1,080, you’ll be hard-pressed to tell apart a photo taken with the Pixel from a photo taken with the X100F or the Ricoh GRIII. That’s the triumph of Google’s computational photography. The Pixel 4 was never meant to be a great camera: It’s a great phone which produces excellent images. P.S.: All images in this piece have been snapped with the Pixel 4. They’re all heavily edited (and some heavily manipulated). If you’re interested in a closer look at my creative process, follow me on Instagram.