But does such an approach actually make a real difference to air pollution levels? Let’s take a look:

What’s the problem with cars?

You probably know the stats, but let’s take just a quick refresher. According to joint research from Harvard University and various UK universities, more than 8 million people died in 2018 from fossil fuel pollution. In fact, the researchers estimated that exposure to particles from fossil fuel emissions accounted for 18% of total global deaths in 2018 — a little less than one out of five. Not all emissions are from cars though. Industrial manufacturing, oil refineries, natural events like weather, dust storms, bush fires, and agricultural activity all contribute to pollution levels. But 2020 research revealed that 41% of global transportation emissions are from ICE (gas) cars. The older the car, the worse the pollution. But things aren’t quite that simple.

EVs aren’t blameless

It’s not just exhaust fumes from ICEs that are to blame. In fact, 55% of roadside traffic pollution comes from non-exhaust particles from both kinds of cars. Of this, around 20% comes from brake dust, which, when inhaled, can cause significant respiratory problems. So unsurprisingly, there’s a big push to get cars (and trucks, as much as is practical) out of high-traffic inner urban areas altogether.

What are some initiatives?

Madrid and London have ultra-low emissions zones, eliminating most gas-powered vehicles made before 2000, and diesel machines made before 2006 from their centers. In London, the city charges drivers with high-emission vehicles a $15.40 fee to drive inside the zone. Again, while EVs are far better, they are still a problem in high concentration. Another approach is to make driving less appealing by limiting parking. In 2016, Oslo removed parking from much of the city, including the center. The Urban Environment Agency shows it got rid of 4,775 parking spaces, replacing most with bicycle lanes. Some cities, such as Paris, ban cars on particular days of the week or only on high pollution days.

Ok, that all sounds pretty good — what’s the problem?

The issue is displacement. Unless there’s the appropriate transport infrastructure, by moving cars out of cities we’re simply transferring the problem somewhere else. There are a few good examples in the UK.

Living on the perimeter of low emissions

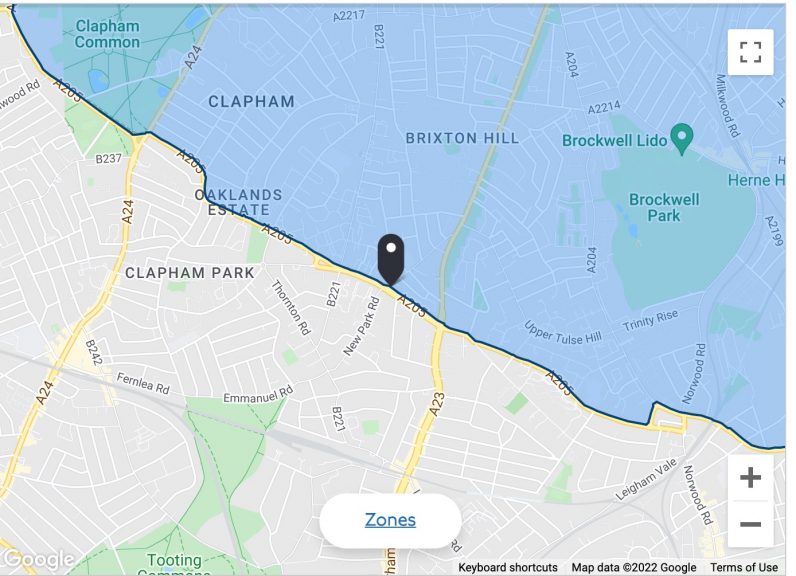

In 2020, a coroner made UK legal history by ruling in a coronial inquest that air pollution was a cause of the death of nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah. Specifically, her death in February 2013 was caused by acute respiratory failure, severe asthma, and air pollution exposure. Prof Stephen Holgate, an immunopharmacology and consultant respiratory physician of the University of Southampton, was part of the case. He attributed Ella’s worsening asthma to the cumulative effect of the toxic air Ella was breathing. Ella lived within 30 meters of the South Circular Road, which caused her final acute asthma attack. This map signifies where South Circular Road sits. Just on the perimeter of the ultra-low emissions zone and next to a freeway. Let’s face it, living that close to a motorway makes it hard to address pollution. It is also possible that traffic increases around the perimeter of cities as people look for payment-free routes. Some states, like California, actually mandate that homes near freeways must come with indoor infiltration systems. Other cities, like Seattle, are exploring construction like “freeway lids” to reduce air and noise pollution.

Park and ride

Another initiative to get cars out of congested cities in the US and UK is “park and ride”. It’s a pretty simple idea. Car parks are situated outside the city center with regular buses or trains into the center. However, this creates more traffic around the local area at peak times. Especially considering that most people choose to live outside cities and large towns, because it is less congested and built up. Like the perimeter of low emission zones, pollution just shifts to this area and the people who live there.

Is the solution to expand car-free zones?

Yes and no. There are actually a bunch of different actions required. For example, in London, the local government identified 12 pollution hotspots that needed immediate attention. They replaced buses in these areas with those that either meet or exceed ULEZ standards. The city has also invested in expanding its electric bus fleet and rolled out thousands of electric taxis and vehicle charging infrastructure. Other efforts have included car-free days and the School Streets program, which closes roads around schools to vehicle traffic at pick-up and drop-off times to encourage walking and cycling. According to the City of London, it has rolled this out successfully in 380 locations, leading to a 97% reduction in schools that exceed legal pollution limits.

Don’t forget about trucks and vans

Equally important is eliminating as many trucks from inner urban areas as possible. In other words, fighting pollution is not just about eliminating cars. Research by Vanarama in 2019 found that 520,000 UK van drivers typically spend over 20 minutes looking for a parking space for each delivery they make. This leads to one hour and 40 minutes of searching for parking every day. That’s a lot of unnecessary driving and idling. An alternative is delivery cargo bikes which reduce the need for inner city vans for short-haul trips. So, air pollution is a complex beast. Car-free cities can help bring down pollution but thinking they’re the be-all and end-all of making places safer to live is flawed. If we’re really going to make urban centers that work for everyone, we need to look at every part of a city – and it’s outer areas. This is possible — but it’s not gonna be easy.