But it all changed this April, when Iraq hosted its first ever nationwide hackathon. The aim was to bring together aspiring entrepreneurs, and solve some of the pressing issues faced by the country through innovation. Organized by the Iraq Technology and Entrepreneurship Alliance (ITEA), the event saw a collaborative effort between 700 youth activists across the cities of Erbil, Baghdad, Basra, Sulaimaniya, and Mosul. Between developing plastic recycling solutions, creating bicycle stands for university students to combat congestion, and developing 3D projections and installations for Erbil’s Citadel, they are part of a blooming tech ecosystem of Iraq that aims to bring about meaningful and lasting change in the region. With a population of nearly 40 million — of which almost half is below the age of 20 — Iraq is home to the world’s fifth largest proven oil reserves, and boasts a GDP of $225 billion (for reference, the US’ GDP in 2018 was $20 trillion). But corruption and a series of conflicts have plunged the country into chaos, severely curtailing its economic progress. That hasn’t deterred people, though. Facing an uncertain future and trying to extricate themselves from the shackles of war, more young minds are beginning to look at entrepreneurship as an opportunity to reach beyond the country’s ailing public sector.

A long road to recovery

On March 19, 2003 at 21:00, bombs began falling on Baghdad. As explosions continued to rock the Iraqi capital, then-US President George W. Bush announced, “At this hour, American and coalition forces are in the early stages of military operations to disarm Iraq, to free its people and to defend the world from grave danger.” What started as a quick attack to overthrow Saddam Hussein and uncover weapons of mass destruction became a nearly nine-year-long conflict marred by insurgent rebellions and eruptions of sectarian violence. It eventually caused more than 150,000 deaths, and cost trillions of dollars, the repercussions of which continue to reverberate across the region, and affect thousands of families to this day. The seemingly endless cycles of warfare have triggered a massive humanitarian crisis, with over four million people internally displaced in the country. Even after a three-year military campaign to drive Islamic State (IS) and its subsequent defeat, Iraq has continued to grapple with political, sectarian, and internal conflicts, fueling the spread of extremism. For instance, the elections that followed were meant to usher in a new chapter of democratic governance in Iraq. However, widespread corruption and failure to address urgent economic reforms have threatened the country’s long-term stability. Credit: Saïna Seedorf / TNW Next, the opening up of Iraq’s enormous oil reserves to foreign players following the fall of Saddam Hussein regime was supposed to herald a new era for the nation, help reignite its economy and potentially transform it into an economic stronghold. Again, the reality was something different. “Ordinary Iraqis have seen little or no benefit from the proceeds of the country’s multibillion-dollar oil industry, much of which has been siphoned off by corrupt politicians,” wrote Ghaith Abdul-Ahad in an extensive feature for The Guardian last year. “Across the south in recent months, simmering anger over corruption and unemployment has been fueled by the dire state of public services, regular power cuts and water shortages.” The unconducive business environment hasn’t helped Iraq either. The country ranked 171 among 190 economies on a leaderboard tracking the ease of doing business, according to data compiled by the World Bank. The Iraqi government has made billions exporting oil, and in the process, turned it into the fifth largest oil producer and exporter worldwide. But the public sector employed only about 2.89 million people as of last year. With the country facing a jobs crisis of unprecedented proportions, and private sector job opportunities drying up with the arrival of Islamic State, youth unemployment still stands at a staggering 36 percent. Rebuilding homes, hospitals, schools, roads, businesses, and telecommunications will therefore be crucial to providing jobs for the young, reversing displacement, and putting an end to decades of political and sectarian violence. But there might still be hope.

The changing tech landscape

Iraq has been more synonymous with corruption and ruinous conflicts than economic progress — but now that the security situation has improved and the economy is slowly bouncing back under the current government, a small community of entrepreneurs, investors and international nonprofits are working to build up an ecosystem. The country, once seemed a lost cause, is staging a resurrection. It’s no surprise, then, that donors and investors thronged the Iraq-reconstruction conference held in Bayan, Kuwait last year. Iraq received pledges of $30 billion, mostly in credit facilities and investment, from neighbors including Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Coworking spaces like TechHub and The Station have mushroomed across the country. Re:Coded, a nonprofit organization that aims to train conflict-afflicted youth to enter the digital economy as software developers and tech leaders, set up its base in Erbil. And last year, TechHub co-founder and entrepreneur Mohammed Khudairi launched Iraq Tech Ventures (ITV) to facilitate a mechanism for international investors to invest in Iraqi startups. “We wanted to build a tech ecosystem in Iraq,” says Hal Miran, who co-founded TechHub, the first coworking space based in the city. “We created TechHub to give budding Iraqi entrepreneurs the impetus they need to build, launch, and grow their startups by providing a vibrant, collaborative workspace.” From providing office facilities to mentoring, access to business contacts, and networking, TechHub aims to be the one stop shop for all startup needs. In addition to being a hub for startups, Miran said TechHub is used to conduct training programs that aim to teach displaced people skills they would need to bring their ideas to life. But Miran acknowledges it’s not yet the best possible environment for startups. “There is no access to proper funding, the infrastructure is still not yet there, but there is no doubting the potential in the future,” he says. Another popular shared space for innovation in Iraq is The Station. Founded in Baghdad in early 2018 by Mujahed Waisi and Muhannad Munjed, it’s already home to about 15 startups.

The mobile revolution

One among several positive outcomes of the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime was the rapid proliferation of technology across the country. Nearly half of Iraq’s population now has access to the internet, with almost every 87 out of 100 people having a mobile cellular subscription. Post-IS Iraq experiences freedom from state censorship, unfettered access to the world, and a life that is mostly free from state interference. The increased internet and mobile penetration has been a lifeline for several startups that have begun operations over the last couple of years. Want to order items online? Miswag can take care of that. Need dinner delivered from nearby restaurants? There’s Brsima and Talabatey. Out of groceries? There’s Erbil Delivery and Mishwar to sort you out. Ship items outside the country? There’s Shiffer. Want to hail cabs? Obr Taxi‘s got you covered. Looking for jobs after graduation? There’s Opportunity. Need books and gadgets within 24 hours? Dakakenna is the place to go. “I always wanted to build something successful in Iraq,” says Yousif Alneamy, who launched Dakakenna along with his friend Abdulrahman in August 2018. The service currently operates out of Mosul, one of the cities that was captured by IS in 2014. Iraqi forces would launch an offensive subsequently in October 2016, and succeed in their efforts to free the city almost a year later in July 2017. “It’s challenging to be your own boss, but I always liked being an entrepreneur,” Alneamy said. “There’s still a lack of knowledge when it comes to running a business in general. I had to learn it all by myself.” With fears over landmines planted by IS, movement in the city is still restricted, and jobs remain scarce. Dakakenna has taken advantage of the situation to build a fairly successful ecommerce model. The suppliers are all currently located in Mosul, which enables the company to handle same-day deliveries. Alneamy explained: But Alneamy, who graduated from Mosul University with a software engineering degree, admits they’re not quite there yet. “Logistics is a major problem. Right now we’re hiring our own drivers to get around the city.” That’s not all. There are also other challenges. Convincing customers to pay online is one. Most services today rely almost entirely on cash for day-to-day transactions.

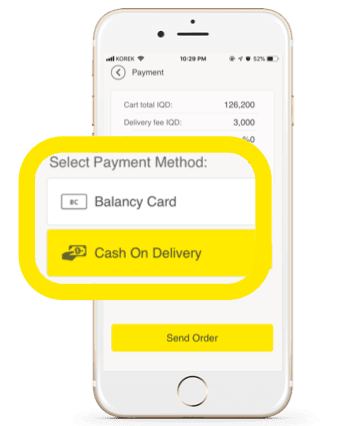

— iraqtechventures (@iraqtechventure) May 12, 2019 The reason? People’s distrust in the banking system. According to a report issued by the country’s Central Bank in 2017, 93 percent of Iraqi adults do not have a bank account. Decades of economic sanctions followed by Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and restrictions placed on withdrawals by Saddam Hussein’s government in its aftermath have made people reluctant to save their deposits in banks. The arrival of IS only made it worse, as people worried they would no longer be able to access their money, or withdraw cash while there was still violence in the streets. “Iraq is very much a cash society,” says Dana Sabah, who founded the grocery delivery service Erbil Delivery in the city last July. “The distrust with the banking system still persists and so the concept of software as a service (SaaS) doesn’t exist. There are no subscription models.” Sabah, who has a management degree from the University of Picardie Jules Verne in Amiens, France, discovered grocery delivery was a space that needed filling. “I was shopping the same thing over and over again, and I realized I wasn’t alone. People were queueing up in supermarkets. That was a sign there was a demand.” “We didn’t know whether people would be interested. So we built an MVP,” says Sabah. MVP — meaning minimum viable product — refers to a product that’s been developed with just enough features to satisfy early customers, and to provide feedback for future product development. Sabah, a graduate of electrical engineering from Salahaddin University-Erbil, is no programmer himself. He outsourced the work to an app development team based out of Erbil. In the year since its launch, Sabah says it’s been a great experience. “There are difficulties, of course. We don’t go to IS areas. Our delivery bikes are not allowed in some places, prompting us to serve customers through cars.” Then there is the aforementioned mobile payments problem. But to get around it, Sabah came up with a solution — Balancy Card. It functions exactly like a mobile top up voucher that adds to customers’ credit, allowing them to pay for items using the card instead of cash. Mobile operators like Zain and Asia Cell have also tackled the problem separately. The largely unbanked population has made Iraq a fertile ground for mobile wallets, with their solutions — Zain Cash and Asia Hawala — gaining traction as an alternative to traditional banking.

A bureaucratic quagmire

There may be a mini tech revolution underway — a parallel Iraq where a thriving entrepreneurial culture has taken root — but it’s still in its nascent stages. Complicating matters is the current bureaucratic atmosphere, which imposes extensive requirements to set up and maintain companies. The lengthy procedures have placed huge financial and operational demands on these startups. As a means to stimulate the unemployed youth and create jobs in the private sector, the Central Bank, in 2015, announced a trillion dinars ($840 million) initiative to finance small and medium enterprises (SMEs) at subsidized interest rates. But loan repayment restrictions — high collateral and immediate high returns in the form of interest payments or dividends — have made it prohibitive to startups. “There are no real places to ask for investment,” says Sabah. “There are not enough accelerators. We need more organizations like Re:Coded. We need someone to tell if it’s a shitty idea. We need more mentors who can guide us in the right way.” Re:Coded, which launched as a pilot program incubated at New York University (NYU) in 2016, offers coding and startup training programs to conflict-afflicted youth in Iraq, Turkey, and Yemen.

— Danar Kayfi (@DanarKayfi) April 26, 2019 It was also instrumental in hosting Iraq Innovation Hackathon, the first nationwide code fest in Iraq. Organized in collaboration with other coworking spaces in the region and Five One Labs — a startup incubator that helps refugees and conflict-affected entrepreneurs launch and grow their businesses in the Middle East — the intent was to vote for the most pressing issues in various cities, and use technology to solve them. Winners walked away with seed money to the tune of $3,000, and access to further mentorship to develop their idea into an actual solution. Founded by husband-wife duo Marcello Bonatto and Alexandra Clare, Re:Coded has partnered with a network of investors and opened a coworking space in Erbil with an aim to support startups through coding bootcamps and a tech startup academy. “I saw millions fleeing Mosul after it was taken over by IS,” says Clare. “Most of the young people I encountered had advanced degrees. Yet they didn’t have access to proper job opportunities, or chose to wait for traditional jobs in the public sector.” She said Re:Coded started as a means to incentivize Iraq’s tech ecosystem and build talent among youth so that they can solve local issues using technology, and be ready for the jobs of the future. Alneamy concurs. The Dakakenna founder says he has frequently fielded job-related questions from Mosul University graduates. “There is a mindset today of pushing them into looking for a government job. It’s so difficult to break this conditioning.” Even then, Clare admits the startup environment can be difficult. “The process of registering a startup in Iraq is often onerous, prompting some of them to incorporate their companies in Dubai instead. This has to change.”

Technology as a transformative enabler

What’s required then is a fundamental cultural shift to encourage the country’s entrepreneurial spirit. In countries with a flourishing startup culture, capital is provided through an ecosystem of angel investors, venture capital firms, and private equity funds. There’s no doubt these mechanisms require the introduction of new laws, regulations, and policies. But time is of critical essence, as there’s an immediate and growing need for such long-term capital. “If there’s enough political motivation, and an overhaul of existing laws, that will be a huge enabler in encouraging people into entrepreneurship,” says Bonatto. Iraq’s challenging environment means that the sustainability of startups is often fraught with uncertainty. But it also uniquely positions local startups to fill up a vacuum that would’ve been otherwise a playground for foreign players. “It’s not a bad idea to mimic global businesses here,” says Clare. “These ‘copycat’ solutions — food delivery, e-commerce, and so on — haven’t been replicated in the local ecosystem. There is a massive potential for growth, including areas like banking, energy, mobility, and waste management. Indeed, one of the solutions that emerged out of the Erbil leg of the hackathon was R3 — an integrated plastic recycling solution connecting citizens to recycling plants via freelance drivers. The platform also encourages members to recycle through rewards like Zain Cash or Careem credit. Speaking of Careem, the ride hailing service — which was acquired by rival Uber earlier this year — is the lone international exception. The Dubai-based company launched its services in Iraq early 2018, and now operates in Baghdad, Najaf, and Erbil. “Careem offers a great service, so much so that it has already decimated local players,” says Sabah. “If we want to compete with them, we need to be strong local players.” This necessitates a better understanding of the market and its demographics, an area where Re:Coded hopes to step in and offer help to aspiring entrepreneurs. “Most people come up with great ideas,” says Bonatto. “But it requires more than an idea to get it to the market. This will take some time. Part of it requires educating Iraqis about the digital economy so that they can embrace the marketplace.” But it also goes without saying the infrastructure has to improve. Electricity blackouts are a major issue, as are internet outages, threatening economic development and fragile social stability in the war-torn country. “We didn’t have any sales for one whole week because there was no stable internet connection,” says Alneamy. “We want to provide a reliable service, we want customers to count on us. But when such outages occur, it makes us question if we should shut shop and try something else.” Careem, on the other hand, has got around internet interruptions by allowing people to call a phone number and make ride bookings via WhatsApp. But Alneamy has no plans of giving up. He is looking at expanding Dakakenna to other cities in Iraq, and possibly neighboring countries, along with talking to more suppliers to come on board the platform. For everything that has gone wrong in Iraq, the country appears to be finally ready to shed its trauma of conflict, and strive towards an entrepreneurial revival that has provided the youth with an opportunity to create exciting new businesses. “This is just the start of what is a very promising phase in Iraq,” says Bonatto. “There’s still a long way to go, but if there’s enough momentum, these solutions can have a transformative impact on the lives of people.”