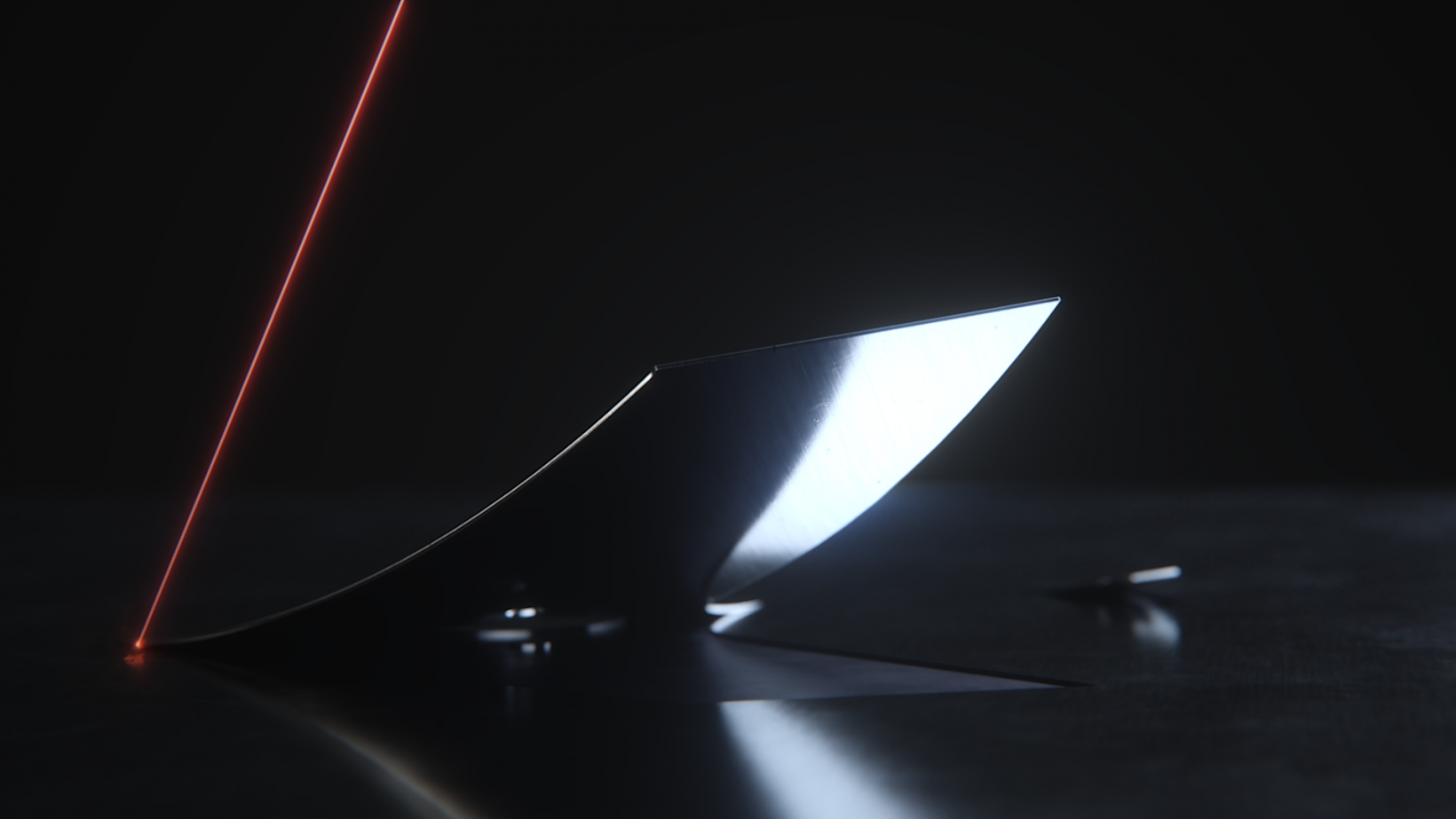

Sweden’s first astronaut and the European Space Agency (ESA) this week unveiled a new project inspired by the paper-folding technique. The program will use technology designed by Stilfold, a Swedish startup that’s pioneered a manufacturing process called “industrial origami.” The technique uses robotic arms to fold sheets of steel over curves to form complex and lightweight shapes. Stilfold previously used the approach to build an electric scooter. According to the company, the techniques resulted in 70% fewer components, a 40% reduction in weight, 20% lower material costs, and 25% lower labor costs. The team believes such savings could be particularly powerful in space, where they could allow complex structures to be constructed with minimal materials and components. In addition, the method doesn’t require any stamping or welding. Stilfold co-founder Jonas Nyvang envisions unfolding vehicles and food storage facilities in outer space. “You can’t bring much to space, because it takes up limited room,” he told TNW. “The flexibility of our technology makes it possible to bring stacked sheets that you can store easily, and then create stuff by unfolding it when you’re there.” To test the theory, Stilfold will work with Sweden’s International Space Asset Acceleration Company (ISSAC), a new organization backed by the ESA and Swedish astronaut Christer Fuglesang, The team will now spend 12 months exploring the possibilities. Nyvang was previously a marketing director at fashion brand Björn Borg, where he worked with the ESA to develop heat-resistant underwear for steelworkers. After founding Stilfold, he was drawn to the ESA’s approach of “spinning-in” space tech to Earth and “spinning out” Earth tech to space. “What’s great about the space sector is it’s pushing the boundaries of material creation for different innovations, because there’s such a rigid framework for what you can do up in space.” NASA has also experimented with techniques inspired by origami, but these projects have focused on big structures. “There’s great potential for smaller structures as well — and that’s what we want to explore first,” said Nyvang. Stilfold also provides an example of how European startups can get involved in spacetech. Stefan Gustafsson, a commercialization officer at the ESA, has the following advice for companies that want to work with his agency: “Firstly, check what a nearby ESA Business Incubation Centre can offer. Startups younger than five years may benefit from up to two years of business incubation, with access to technical, financial , and IP support, as well as €50,000 of funding,” he told TNW via email. “Next to this, there are various ESA programs that could be attractive for SMEs, e.g. ESA Business Application Kick-Starters that provide funding for companies developing space-based applications. ESA has a patent portfolio with technologies which may be useful in another context. “Finally, ESA’s SME office also has various ways of supporting startups too, e.g. getting training to apply to regular ESA contracts.” There are no guarantees that they’ll get backed by ESA, but getting their tech in space doesn’t have to take light years.